Jul 23, 2012 “Give Up Tomorrow” is taken from an interview with Paco who said that his main tactic of survival while in prison was living day to day, “worrying only about how I was going to survive that day.” He told his companions, he said, to “give up tomorrow,” and concentrate on living only for the moment. Give Up Tomorrow is also an intimate family drama focused on the near mythic struggle of two angry, sorrowful mothers who have dedicated more than a decade to executing or saving one young man. Their irreconcilable versions of justice play out in a controversial case, dubbed 'The Trial of the Century', that ends a country's use of capital. Give Up Tomorrow exposes shocking corruption within the judicial system of the Philippines in one of the most sensational trials in the country’s history. Two grieving mothers, entangled in a.

Pamela Cohn meets Michael Collins and Marty Syjuco, the partners behind Give Up Tomorrow, the documentary behind an international human rights movement.

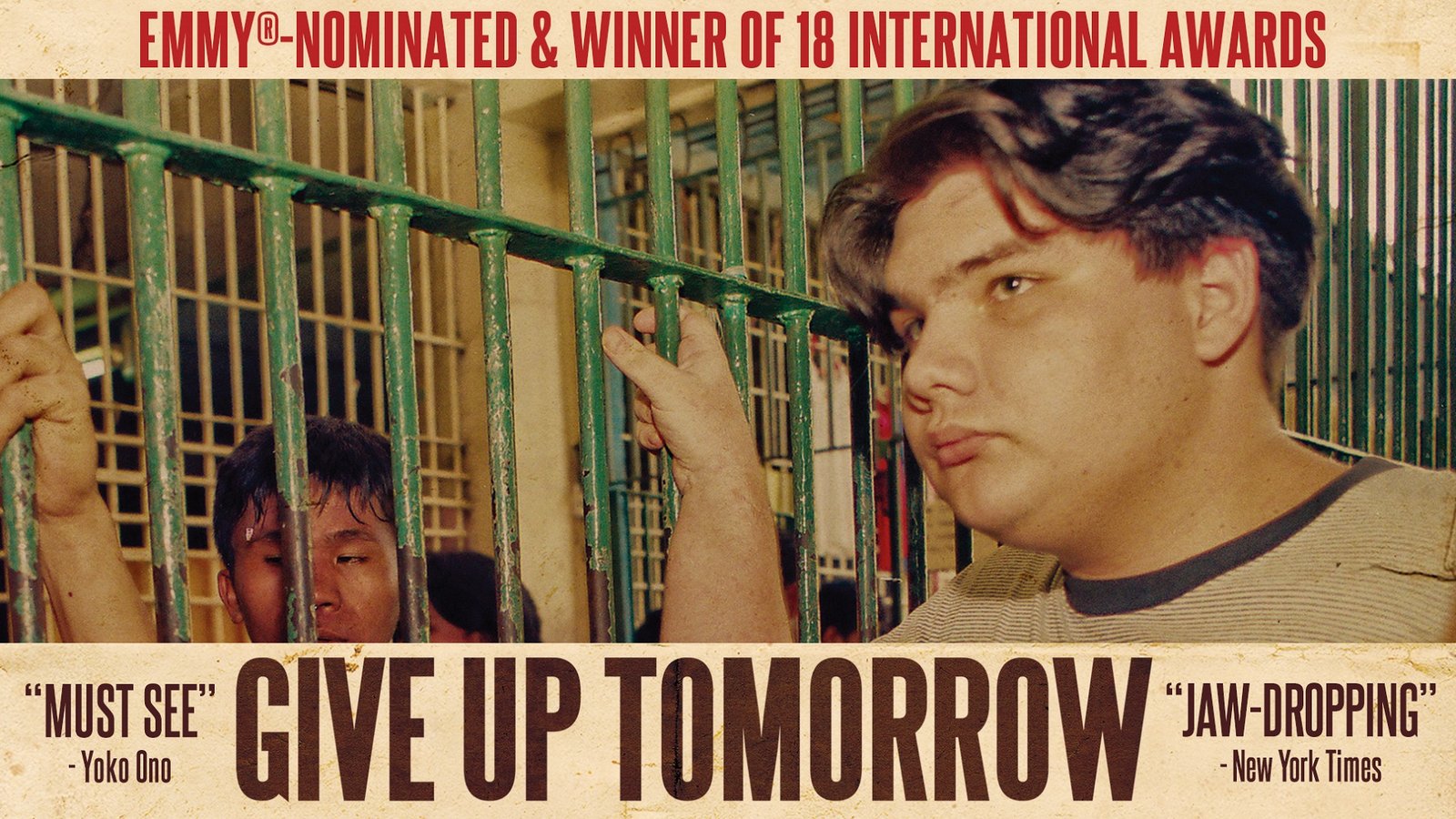

Give Up Tomorrow, 2011. All images courtesy of Marty Syjuco and Michael Collins.

For his first feature, the hugely ambitious documentary Give Up Tomorrow, director Michael Collins did not flinch when faced with an exceedingly complex story. An award-winner since its premiere at this past year’s Tribeca Film Festival in New York, where it won the Audience Award, as well as a Special Jury Prize for New Director, the film also won an Audience Award at Sheffield Doc/Fest in the UK, and Best Activism in a Foreign Documentary at Michael Moore’s festival in Traverse City, Michigan.

Give Up Tomorrow Full Movie

Collins and his partner and producer, Marty Syjuco, have just spent the past week with their main protagonist’s parents, sister and cousin in Valladolid at the Seminici Film Festival in Spain, the country where Paco Larrañaga is currently incarcerated in a maximum-security prison serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. Larrañaga was a student who—fourteen years ago, in July of 1997—was accused of the murder of two young sisters on the provincial island of Cebu in the Philippines. Give Up Tomorrow meticulously presents the gross miscarriage of justice Larrañaga underwent at the hands of the Philippine government, in addition to being tried and convicted by the tabloid press there before the court had even handed down a verdict.

The filmmakers are also spearheading a massive, international human rights campaign that has seen tens of thousands of people get behind Larrañaga’s case, pleading for his release from the Spanish government. Using his Spanish birthright, Larrañaga’s family was successful in moving the young man from the Philippines where his life sentence had been elevated to the death penalty. However, he is still sitting in prison patiently waiting for justice to prevail. Give Up Tomorrow is a powerful dissection of the events that led to Larrañaga’s incarceration. It is an expertly produced piece of work, suspenseful, gripping and ultimately, heartbreaking.

Back in July, I had an opportunity to sit down with Collins and Syjuco for a long chat when the film played at Dokufest, the International Documentary and Short Film Festival in Prizren, Kosovo. Every long interview I’ve done in Prizren has been accompanied by ice cream, for some odd reason, and this time was no exception. As we sat over giant sundaes in a café near the riverbed cinema, the filmmakers talked to me about this extraordinary journey, seven long years in the making.

Pamela Cohn For a first film, Give Up Tomorrow has a lot of sophistication in its storytelling style. It’s a very deep emotional journey, which is very hard to accomplish while swimming through an extremely complex set of circumstances. You had to craft a film that not only had to clearly explain the complicated details of a legal case, but also were tasked with trying to illustrate a profile of an entire culture.

Michael Collins The film really came to life in the editing process for us. Our approach for this was always, “We’re making a film.” Yes, this is an incredible injustice and an incredible story, but we did not really want to approach this as an advocacy film for this cause. We knew by making a good film, the truth would emerge and that people would align themselves; they would want to fight this injustice the same way we did. What we kept coming back to in the edit room was trying to return to that place that inspired us to pick up a camera in the first place. I felt a real personal connection with Paco, to be honest with you.

PC He is a protagonist that one connects with deeply almost immediately. He’s a compelling screen presence.

MC My introduction to Paco was through a request to do some kind of animation project. I went to art school where I studied computer animation, photography and video art at Syracuse University [in New York] at the School of Visual and Performing Arts. I was an art director at a small communications company but was about to quit. Marty and I had been together a couple of years at that point. It was 2004 when Paco’s sentence was elevated to death. Marty didn’t really know much about what was going on, but from time to time he’d mention that something had happened to his brother’s wife’s brother. But it was really cloudy. No one really knew what happened but everyone was just waiting for the Supreme Court to fix it. It was a limbo period.

Marty had been living away from the Philippines for a long time, so he didn’t really know the particulars and we didn’t talk about it much at all. It was a very complicated thing to have to explain and the family was very quiet about it. But when Paco got the death sentence, his brother came to us, desperate. He asked me to create an animation for a web site that would illustrate some of the injustices that had happened during the trial. I needed to learn about the case and discover whether I felt that Paco was innocent or not, so asked him to send me some information. He sent me a letter from the “Unheard35,” the witnesses who weren’t allowed to testify who were with Paco the night of the girls’ disappearance. This is what they had started to call themselves. Point by point, the letter describes what happened, whom they were with in Manila, the photographs that were taken. They went to court and the judge did not let them testify. They went to the media and no one in the press listened to them. And Paco is sitting on death row. I was sitting in a café in the East Village while reading this and I just started weeping because it was so heartbreaking, the way they described in detail the injustice of it all. Paco, at that point, was my age. He was 19 when he was arrested and this was seven years later. For the past seven years of his life he had been in prison and seven years before that moment, I had moved to New York City.

PC You had a sense of what that amount of time felt like.

MC Yes, the time I had grown and changed and what all that meant, being in your 20s and out in the world on your own. I told Marty we had to do something. No one’s going to do anything; this guy is just going to languish in prison. We did some research and some soul searching, checked our bank account and our credit line, quit our jobs, bought a camera, and jumped in. Our first trip was to LA where two of those witnesses were living. After meeting with them, we just knew that this story had to be told. It was mind blowing, like a Kafka novel, the kind of thing you couldn’t even dream up.

PC Marty, as the producer, when did you realize that this was going to be a very long-term project? When did you start to think about bolstering your efforts to go beyond self-funding the project? Even the most intrepid DIY filmmakers reach a point where they know that in order to craft the kind of piece that’s envisioned, one has to think about other resources.

Marty Syjuco My background is more on the business side of film. I was working at Focus Features in distribution. During production, I knew that it was possible for Michael and me to self-finance. Our biggest investment was the camera and our travel costs. But I have family and friends in the Philippines, and we stayed with them, borrowed cars and equipment, getting by with the generosity of other people for the first couple of years. Once we had enough footage to assemble a trailer, we started including that with our proposals and thus began the process of fundraising. We had enough to solicit for funds and that, in and of itself, was its own journey. The whole ITVS process, to which we applied four times, really helped us since we were still finding the story, the path. As Michael said earlier, the story of Paco is so dense and complex. At that point when people asked us what the film was about, we still didn’t know because it’s about so many things.

In its finished form, it’s the journey of this family and their struggle to find justice for their convicted son. It was a long exploration.

MC We were investigating. That was our approach. We could clearly pinpoint the injustices that happened during the trial but it was so much bigger than that—politics, corruption. The Philippines is a complex place. We did one entire trip where we just interviewed historians just to get a grasp. Even though we didn’t use that in the film, it was such a vital part for me in deciding how to craft this. Marty is from there, but I had to take great care to understand the complexity. It all plays into what happened to Paco, this country being a post-colonial place, its history with Spain, its history with the US, what happened to the justice system there with Marshall Law under Marcos—all of those things are very important to understand.

PC Did you edit as you were shooting? It’s told in a pretty linear way, which considering the complexity of it all is a smart choice. Instinctively, did you know from the beginning that you were going to go for this strong emotional through-line? The reason I ask is that the audience spends a lot of time with the mothers—the mother of Paco and the mother of the missing girls. These women are parallel touchstones in terms of the culture and the circumstances in which they find themselves. It grounds the film firmly in the realm of the family and this is one of its biggest strengths. Tell me a bit about growing your relationships with these women as they were going through immense trauma. You can only deal with pure emotion for so long; sooner or later, you have to contextualize it, otherwise it just becomes some sort of soap opera.

MC That was definitely the biggest challenge—how to have both a plot-driven film and a character-driven film. It’s already heavily plot driven due to the complexity of the story. In earlier cuts, the film became so dense and informational—it was exhausting to watch. That’s when we went back to our experiences shooting in the Philippines, those moments when I’d come home after shooting with these women and be emotionally exhausted, being around people who were so victimized, both families, the Chongs and the Larrañagas. If we’ve allowed people to experience walking in their shoes just for a bit, then we’ve done our job. We can list every single injustice that occurred and it would be upsetting and there would be an audience for that. But we hope what makes this film reach beyond that audience is the universal part of the story, the human experience that the families bring to it. And while they’re both faced with extreme tragedies, in terms of how they deal with it and their singular experiences, they are very different. It was very delicate.

PC I think the delicacy, for the most part, probably stemmed from the fact that you were making this film believing in Paco’s innocence. You then had to get close to a woman who was convinced that he was, indeed, the man that had raped and murdered her girls. The bedrock of Mrs. Chong’s truth lies in the belief that Paco is guilty and that he should die for his crime. As a director, how did you separate? Exposing yourself to this time and time again over a course of years must have been difficult.

MC Yes, it was. It was extremely difficult for me to decide how to handle Mrs. Chong and be in her presence. I was editing samples over and over again for different grant applications while we were still shooting so I was already handling the material and handling her as a character. I was so wound up in this emotionally; it was extremely hard to separate. I was enmeshed in the archival and I would watch her categorically lie over and over again, seeing the damage that these lies had caused. There were people on death row! I had this real animosity towards her but I knew that I had to get over that. Part of my own journey was going and sitting with her, interviewing her and coming to the realization that she is the first victim. She didn’t handle herself well through all of this. But her two daughters went missing and her reality was shattered. And then, her reality was built back up again in a way that was harmful to other people. It wasn’t so much for me to judge, as it was for me to understand and try to represent that on screen. I have to see her as another victim in all this, not some easy villain we can hang all our anger upon. I had to represent her the way in which she represented herself to me.

Our general approach was to give people space to tell their truth, whether we agreed with it or not. The same held true for Mrs. Chong. I did ask some probing questions that had to be asked. But she would always deflect them in a somewhat whimsical way and go right back into her version of the story. Truthfully, I wasn’t very confrontational or interested in ambushing her in any way. Aside from Mrs. Chong, we also interviewed members of the police force and the prosecutors, a lot of people who had a lot to hide and who were lying to us. We would gently confront them by telling them what we had learned and they would be dismissive. The media had never confronted them and they never thought this was ever going to come back to them.

PC Talk a bit about how complicit the media circus was in all this since this is an integral and key part of the story. Marty, being from that culture, you grew up with this kind of tabloid-esque way of handling criminal cases—well, in fact, we all have from whatever culture we’re in. But there were serious breaches, the most staggering that of making and airing on national television a docudrama of the murder which fingers Paco as the perpetrator.

MS Yes, of course, the media was totally complicit. Paco and his co-accused were tried by the sheer publicity of all of it, including that docudrama. Before, I would read the newspapers and believe everything I read, before my experience with this case. The media goes unchecked, especially in the Philippines. It’s a bit more complicated, however. There, the journalists are in danger. There is the highest incidence of journalists being killed there, second only to Iraq. One journalist in the film, the young woman who appears in the beginning, received death threats. It’s a culture where media can be bought or bullied.

In this case, the complicity was even more pronounced because it was such a high-profile case. Having Paco on the front page sold a lot of newspapers. For that program we mentioned, the TV ratings were high; it starred a famous actor playing Paco and it took place during the trial—let me emphasize, before any decision by the judge, or any conviction was handed down. Before the defense had their say in court. So it shows someone called “Paco” raping and murdering those girls. They didn’t have a chance.

MC Something about the media specific to this case was the President of the Philippines, Joseph Estrada, who had a very keen interest in getting these young men convicted. His personal secretary is Mrs. Chong’s sister and she showed up at news stations. This was what one of the journalists we interviewed informed us. She told them that she was there on behalf of the President’s office and she wanted the story to be reported favoring the Chongs. She boldly made that known. It was as good as a death threat from the leading administration. Now that’s changed, of course, in the current administration, but that’s the way it was then. The drug lords, the mob bosses are not outside criminal forces; they were on the government payroll. In fairness to some of the journalists, they were just purely afraid for their lives to report on the other side.

PC Paco is the central protagonist of this film for a variety of reasons, including the family relationship with you, Marty. What is it about this young man that he became this centrifugal force, not only for your film, but for the whole case?

MC Marty hadn’t seen him since he was a kid and I had never met him. The first morning we were in the Philippines, we went straight to the jail to try and find a way to get in to see him. He was on death row at that point. After a couple of hours, someone came to get us and we were led into this type of dorm, which was pitch black since there’s no electricity during the day. They brought us to the end of this hallway, up a staircase and into this room and there he was. Just being in his presence, you felt safe somehow.

Give Up Tomorrow

He’s the rock in the center of his family. That’s why they’ve all lasted this long. He’s been in jail for close to fifteen years; he’s a survivor and he can take care of himself. In terms of his parents, who are so vulnerable and fragile, this is why Paco doesn’t show a lot of emotion, particularly in front of them. He’s the one that’s always reassuring them that everything’s going to be okay. He’s the one that keeps them all strong.

MS Even though he’s the one locked inside a prison, wrongfully convicted, this is his family. And they are suffering, too, and carry this enormous guilt.

MC Their whole community, the entire country seemed to turn against them. Paco’s mother is a very proud person and also a very private one, honest, hard working. They’ve had to endure so much censure, lies, character assassination—it just goes on and on. Their livelihood comes from their farm in Cebu. They could only afford to go see him once or twice a year in Manila, which is only a one-hour flight.

MS The media was also responsible for misrepresenting who these people are. By no means are they impoverished; they’re solidly middle class. But the media presented them as being rich, affluent, privileged. “The rich are trying to get away with murder,” with Paco as the “scion” of this wealthy family, this clan.

Give Up Tomorrow Full Movie

MC They’ve been accused of paying off everyone, left and right, falsifying documents. Once you see the fragility of these people, you realize how absurd these accusations are.

MS They are, in fact, quite naïve. They trusted the system too much. I’m a Filipino and I know how the system works. It’s not something to be trusted. Either you pay the police to make it all go away, or you flee. Paco had that option. My brother, Jamie, recommended that he do just that. But it was Paco’s mom who convinced him that if he ran, he would always be branded as a criminal when he had no reason to run. She feels tremendous guilt and remorse about that.

PC For such an airtight piece, one can intuit how many pitfalls there could have been in putting something this complex and personal together. Now that you’ve started having encounters and responses from audiences, what do you know about this film that you might not have before?

MC I feel like we did our job. We were, essentially, pulling our hair out right up until the end of the edit, feeling like we’d failed somehow. It just wasn’t working. And then in the last couple of months of the edit, it clicked. When I see people come out from viewing the film and they tell me that they relate to the family, that their hearts break for them—that, to me, is the most important thing. They can also say that this was an injustice and have been schooled in the facts of the case, but that’s secondary.

We had really dense cuts of this film and I was attached to so much of the footage. It was really Eric Daniel Metzgar [an award-winning director in his own right] who helped pull some of that stuff out. He would tell me that there needed to be space for the emotional stuff, and while I never fought that, I was having a hard time finding that balance of exposition and emotion and that took two entire years to accomplish that. It couldn’t have been done any faster. It’s a fourteen-year story condensed into ninety minutes.

PC Well, I can say that after seeing this the first time, I walked out believing that this film might help to free this man.

MC We were with Paco two weeks ago [this past July] and we had an opportunity to get him a copy of the film so he could see it. After watching it, he turned to us and said, “That film is going to get me out of here.” He also told us the next day that of the past fifteen years of his life, the night before—after watching the film—he slept the best he’s slept since being arrested. Of course we want this film to help Paco and the other men that are accused in this case. I can’t imagine having this film out in the world, one that shows such obvious injustice, that he can remain in jail.

MS Actually, we hope we can shed light on other victims of similar injustices and, eventually, the larger goal is to contribute to campaigning for the abolishment of the death penalty.

MC We wanted to make a film that would sustain itself over years. This case, while it’s very specific to the Philippines in some ways, is universal in many others. It’s about the media and what happens when it goes unchecked, when it doesn’t do its job. I believe part of that job is to safeguard human rights. It’s about democracy and what happens when the courts are corrupt. The police don’t have the means to conduct a proper investigation. People are only safe as long as our institutions are above board. When there’s corruption running rampant in those areas, none of us is safe.

We’re launching a campaign called Justice For Paco, Justice For All. We’re setting up partnerships now with Amnesty International, Fair Trials International, Reprieve. These organizations can use this film as support in the work they’re already doing. We’ve been treading in unfamiliar territory since day one. Every chapter in this story, including all this stuff ahead of us, is part of the adventure. We’re letting the film take us where it needs to go and making ourselves available for that. What’s so nice about film is being able to spark conversations about things that are important to us all. There’s no way to measure direct impact, but we can see people becoming more conscious, more aware, more apt to question what they might read in the newspaper or hear on television.

MS Paco is turning 34 this December. He was 19 when he was first arrested. That’s a long time.

MC He’s aged so much the past two years he’s been in prison in Spain. The Spanish government knows he’s innocent; that’s why they brought him there. Yet, he’s still inside. At least in the Philippines, he was around his family. He had some semblance of a life even though it was restricted to that compound. And now he’s alone. So much has been taken from him. I don’t know what else can be taken.

The Free Paco Now website is http://freepaconow.com.

For more on Give Up Tomorrow, visit the film’s website: http://www.pacodocu.com*.

Pamela Cohn is a Berlin-based film producer, curator, freelance programmer and arts journalist.

Related

Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro testifies that James Baldwin’s embattled America is still our own.

Paper Clip is a weekly compilation of online articles, artifacts, and other—old, new, and sometimes BOMB-related.

Montana Wojczuk reviews the documentary William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe.